The long summer of migration has turned into winter. During the first half of 2015, migratory movements opened new ways across the borders of Europe, from the Turkish coasts over the Balkans to Northern Europe. Migration through the Balkans is not a new phenomenon: people denied access to legal routes across borders have long forged their own paths through the region. However, the so-called ‚humanitarian corridor‘, which formed in the interplay of the new paths forged by autonomous movements and governmental responses, began channelling refugees arriving from Turkey on the Greek islands on a state-controlled route over the Balkans to Northern Europe. The paradoxical ‘humanitarian corridor’ developed into a temporary passageway of free movement on the one hand, which has to be seen as a victory, but on the other hand the route quickly became heavily state and police controlled.

Currently, states in and outside of the European Union turn from the regulation of movement across the corridor towards increasing restrictions and segregation based on alleged nationality. On and around the corridor, controls are being re-introduced, new fences are erected, the border is ever more militarised, and those deemed undesired increasingly face detention and expulsions. These political decisions to partially close borders repeatedly create foreseeable crises, but new practices of resistance as well.

The first major restriction on movement on the Balkanroute was the closure of the Serbian-Hungarian border in October 2015. Protests against the closure were answered with heavy state violence. The decision to reintroduce border controls forced refugees coming up from Serbia to swerve west and created a politically manufactured humanitarian crisis at the Serbian-Croatian border. Croatian authorities reacted slowly, and for the first few days, refugees had to cross the border by foot, without adequate infrastructure to meet basic needs on either side of the border. They had to walk 20 kilometers in the freezing rain, through fields and mud with their only foreseeable option of shelter, the police-run camp of Opatovac where they would be processed and given registration cards before being authorized to pursue their route. The border closure and the attempts to manage the groups waiting there for hours created a desperate situation at the Bapska-Berkasovo crossing at the Serbo-Croatian border, a politically manufactured humanitarian crisis created through the control and restrictions imposed on the movement of people.

In the months afterwards, more political decisions to restrict movement along the Balkanroute ensued. On the 18th of November 2015, Slovenia closed its borders for refugees who could not demonstrate that they were from Syria, Afghanistan or Iraq [1]. This created a domino effect in Croatia, Serbia and Macedonia, with each state practicing – either temporarily or permanently – some form of segregation. From then on and as it is still the case today, only people with Greek registration papers stating Syria, Afghanistan or Iraq as a country of origin were allowed to pass the Greek-Macedonian border in Idomeni, the entry point to the Balkanroute. This policy seems to have been pushed by the European Union to slow down or even stop movements along the Balkanroute.

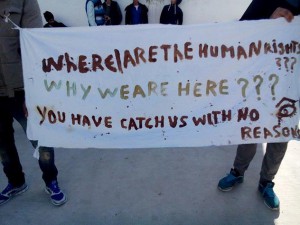

Such practices are in contradiction with the prescription of international law which stipulates that protection should be granted on an individual basis and not based on nationality. The decision to partially close the border created another politically sanctioned crisis. Especially in the first few days in Idomeni, many of those who were not allowed to pass had no shelter, no protection from the rain and cold, no access to enough food. The people who were prevented from crossing the border protested for several days, demanding for the border to be reopened. They shouted and painted slogans, saying ‚Open the Border‘, ‚Stop racism‘, ‚Freedom of Movement for All‘, ‚Nobody is Free until Everybody is Free‘, ‚Where is human rights?‘, ‚We are not terrorists we need Freedom‘, and many more. A group of refugees went on hunger strike and sewed their lips together. At the same time, the militarisation of the border increased; Macedonian military units and Greek police officers were deployed at the border, a new barbed wire fence was constructed along the border, and Frontex established an operational unit. [2] The violence that goes along with border militarisation erupted several times: The border guards repeatedly shot teargas and rubber bullets into groups of refugees trying to pass the border without authorisation. On Wednesday 9th December, 400 Greek riot police officers were deployed to evict the people who were waiting in Eidomeni. The police surrounded the camp, and started pushing people out of their tents and into buses to Athens, 6 hours away from the border. Around 300 people refused to enter the buses, there were protests and several arrests, while media and independent observers were denied access to the camp. Tents of people refusing to leave were cut open and those inside removed. The police operation left empty tents and destruction. The scenery in Idomeni after the evictions was devastating: most of the green tents seemed to have been opened in a forceful manner and inside them the remnants of the activities of the night before were still visible. But messages of resistance also remained in Idomeni.

Most of the people who had been waiting and protesting at the Greek-Macedonian border were temporarily brought to the TaekWonDo stadium in Athens. The stadium was closed after a few days. The ‚options‘ given by authorities to people with Moroccan nationality [3] were detention, deportation, or ‚voluntary‘ return. Around 400 people were detained in the Corinth detention center close to Athens. There were soon protests in the detention center in Corinth. Y., one of the detainees documented life inside the prison-like facility and kept people on the outside informed of the new arrivals of – mainly Moroccan – young men. On the 27th of December, people made banners and protested against their forced detention and the threat of deportation.

On the 3rd of January, there were more protests still and several people tried to break out whilst the Greek police intervened. Then, on January the 5th, what many had feared would start to happen, happened: around 100 Moroccans who had recently been detained in Corinth were taken back to Turkey by Greek authorities. There are reports though, that Turkey did not accept them, and that they are now back in Greece. Currently, smaller groups are being returned to Morocco on IOM-organized flights. Their places are refilled quickly, with around 400 people detained in Corinth all the time. This week, two Moroccans attempted suicide and 100 more detainees began a hunger strike. They are asking for their release and the opening of the border, so that they can continue onwards.

Y., one of the detained people from Morocco, writes letters from and about Corinth [4]:

„The prisoner and his charge are looking for a different life style.

They call me economic migrant, I did not come here looking for money, but for culture, culture of love and equality, for a culture which is far from those of newspapers and fake books, for a culture which is unknown to politicians.

Each of us has his own prison, someday they will understand, that their imprisonment are their offices and ties.“

Of the people with insecure immigration statuses who are not (yet) being detained in Greece, only those who have the financial means to do so can move onwards by hiring the services of a smuggler without any certainty that they will make it to their desired destination. People who are not able to pass at the Idomeni border crossing are still attempting to get onto the corridor, after having partly walked through Macedonia. But the segregation continues on the rest of the route. Still, many people are being pushed back to the Serbian border, following detainment in the Croatian camp of Slavonski Brod. One Pakistani individual filmed his walk back to Serbia in the snow, by the rail tracks (see video below). Another person from Pakistan reported being detained in Šid for 10 days and being pushed back 4 times. These reports come amid other accounts of police violence at times of push backs: children as young as 10 years old, as well as unaccompanied minors are being made to walk back into Serbian territory. Some report being punched in the face and being lied to, led to believe they were walking to Slovenia, when they were in fact walking back into Serbia. [5]

[Video: Walking back to Serbia after being pushed back by Croatia]

[Video: Walking back to Serbia after being pushed back by Croatia]

In order to put all these events in perspective, it is clear that the border regime is becoming more and more restrictive for those migrants considered ‘undesirable’. The looming closure of the corridor is also reflected in the recent announcement from Sweden that it has reached its capacity limit, in addition to Germany’s increased border checks. All this goes on whilst still, people with European passports continue to travel undeterred. In this depressing climate it should nevertheless be noted that state power and control can never be pervasive, and people will keep finding their way through the fences, albeit with more risks for their health and lives. Europe should be building bridges not fences, and constructing homes not prisons. Nevertheless, as it continues to do otherwise, the struggle goes on and solidarity prevails.

[1] Slovenia’s official narrative was that it ‘just’ wanted to return 162 Moroccans on the 18th. This created a panic reaction down the Balkan states. A few days later Slovenia reacted to the accusations of segregation and declared it was not keeping people out of the country based on their nationality. See this link for updated information (18.01.16): http://mobil.derstandard.at/2000029299191/Gestrandet-zwischen-Deutschland-und-Slowenien.

[3] All other nationalities were given the option to claim asylum in Greece or apply for a re-location program to be placed in another EU country.

[4] You can find more of his writings here https://noborderserbia.wordpress.com/2015/12/26/prison-post-4/

[5] https://moving-europe.org/2016/01/06/croatia-slavonski-brod-transit-camp-for-migrants-and-refugees/#more-560

1 thought on “Restrictions and segregation on the Balkanroute: Fences, detention and push-backs”

Kommentare geschlossen.