During the first half of 2015, migratory movements opened new ways across the borders of Europe, from the Turkish coasts and Greek islands over the Balkans to Northern Europe. Migration through the Balkans is not a new phenomenon; people denied access to legal routes across borders have long forged their own paths through the region. However, in October 2015 the so-called ‚humanitarian corridor‘, which was formed in the interplay of the new paths created by autonomous movements and governmental responses, began channelling refugees on a state-controlled route across the Balkans. The paradoxical ‘humanitarian corridor’ developed into a temporary passageway of free movement on the one hand, but became heavily state and police controlled on the other. After a limited time of relatively free passage, the Balkan corridor became more and more restricted to a continuously reduced number of nationalities. Eventually, on 8 March, officials from the countries along the route announced the complete closure of the Balkan corridor, meaning that only those with valid visas could pass the borders. In the ensuing weeks and months, Idomeni became a very visible and mediatised symbol of the inhumane consequences of the European border regime. After much speculation about how long the camp would be tolerated, on 24 May, those who remained in Idomeni were evicted by mass police forces. In this article, we look back on some of the key events of the last few months and conclude with some remarks about the current situation.

The first major restriction of movement on the Balkan Route was the closure of the Serbian-Hungarian border in September 2015. Protests against the closure were answered with heavy state violence. The decision to reintroduce border controls forced refugees coming up from Serbia to swerve west, creating a politically manufactured humanitarian crisis at the Serbo-Croatian border. Croatian authorities reacted slowly, and for the first few days, refugees had to cross the border by foot, without adequate infrastructure to meet basic needs on either side of the border. They had to walk 20 kilometers in the freezing rain, through fields and mud having only one foreseeable option of shelter, the police-run camp of Opatovac, where they would be processed and given registration cards before being authorized to pursue their route. The border closure and the attempts to manage the groups waiting there for hours created a desperate situation at the Bapska-Berkasovo crossing at the Serbo-Croatian border. The control and restrictions imposed on the movement of people resulted in a politically induced humanitarian catastrophe. Nevertheless, the ongoing strength of the refugee movement forged another path across the borders of Europe: Between October and November 2015, thousands of refugees could travel to their desired destinations by train via Croatia and Slovenia, despite the increasingly stringent control system.

The months afterwards saw more political decisions to restrict movement along the Balkan Route. On the 18th of November 2015, Slovenia closed its borders for refugees who could not demonstrate that they were from Syria, Afghanistan or Iraq. This created a domino effect in Croatia, Serbia and Macedonia, with each state practicing some form of segregation. From then on, officially only people with Greek registration papers stating Syria, Afghanistan or Iraq as a country of origin were allowed to pass the Greek-Macedonian border in Idomeni, the entry point to the corridor. The decision to partially close the border created yet another politically sanctioned crisis. In Idomeni, many of those who were not allowed to pass had no shelter, no protection from the rain and cold, and insufficient access to food. The people who were prevented from crossing the border protested for several days, demanding the reopening of the border. While a group of refugees went on hunger strike and sewed their lips together, the militarisation of the border increased; Macedonian military units and Greek police officers were deployed at the border, a new barbed wire fence was constructed, and Frontex established an operational unit. The violence that goes hand in hand with border militarisation erupted several times: The border guards repeatedly shot teargas and rubber bullets at groups of refugees who were trying to pass the border without authorisation. On Wednesday 9 December, 400 Greek riot police officers were deployed to evict the people who were waiting in Idomeni. The police surrounded the camp and started pushing people out of their tents and into buses heading for Athens, 6 hours away from the border. Around 300 people refused to enter the buses, there were protests and several arrests, while media and independent observers were denied access to the camp. People’s tents were cut open by police and those inside removed, leaving scenes of destruction.

For a few weeks after the partial closure of the corridor, a constant number of people were still allowed to pass through Idomeni. However, mid-February saw the beginning of a similar unfolding for Syrian, Iraki and Afghani (SIA) nationals to what had happened at the end of November for the non-SIA nationals. Afghanis were evicted from the camp in Idomeni and no longer let into the corridor, as control measures became harsher and harsher. Syrians and Iraqis could still pass, but in highly reduced numbers, forcing hundreds to set up camp at the border crossing in Idomeni and wait their turn. In reality, this ‘waiting in line’ functioned – at the beginning at least – as a token of hope. As long as some could still pass, even if only 20 a day, there was still hope. Enduring the dire conditions in Idomeni could be done, insofar as it was the price to pay to cross the gateway to Germany. The diminished number of people allowed through, lasted a couple of weeks until finally, on 8 March, officials of the Balkan Route states announced the reintroduction of Schengen and henceforth the closure of the humanitarian corridor.

The eventual closure of the Balkan Route at the Greek-Macedonian border created another humanitarian crisis, making Idomeni the symbol of the inhumane consequences of EU border policies. Thousands were stuck, again – exposed to the weather conditions and insufficient access to basic provisions. But people refused to give up and leave Idomeni. On 14 March, people gathered in Idomeni and started walking towards Macedonia, crossing a river, and eventually the border into Macedonia. However, what started as the second ‚March of Hope‘ soon turned into another instance of restrictive policies of control and closure. In Macedonia, refugees were separated from journalists and independent observers. The circa 2000 refugees, who had entered Macedonia were pushed back to Greece through holes in the fence, group by group, without consideration of their individual circumstances or the possibility to ask for international protection.

The push-back in March was, and to this date remains, the largest and most mediatized one. But it is part of a systematic policy of push-backs: many refugees try every night and many are forced back. With the border closure, the people-smuggling business picked up again and smuggling prices rose, showing just how hypocritical the anti-smuggler rhetoric of EU leaders is. Many of the people stuck in Greece, would have the right to apply for family reunification under Dublin III and everyone would have the right to apply for asylum. However, access to these basic rights is currently denied.

To divert attention away from the situation in Idomeni, the authorities increasingly tried to convince refugees to move away from Idomeni and stay in government-organised and military-run camps instead. However, and contrary to the official rhetoric presenting these camps as a better alternative to Idomeni, the conditions in these camps are humiliating and inacceptable. Instead of agreeing to take the provided buses to the camps, many refugees stayed in Idomeni: self-organising daily survival, trying to cross to Macedonia and protesting repeatedly. In late May, the refugees in Idomeni were evicted for the second time. Police forces were deployed to the area and independent observers were prevented from entering, after several days of restricting food deliveries and electricity cuts. The official rhetoric emphasised that the operation was carried out without violence. But how voluntary could the departure of people have been when there was no other choice and a heavy presence of riot police? Idomeni was a focal point situated right on a border. The removal of the people from this pressure point, makes it more difficult to self-organise close to the border, while making it easier to divert public attention away from the inacceptable situation caused by border closures.

The corridor – with all its restrictions – remains a historical event initiated by the movement of people, which enabled thousands to reach central Europe in a relatively quick and safe manner. Although this passageway is now closed, the struggles of people in Greece and elsewhere for freedom of movement continue. The Balkan Route is not dead but those who travel are more invisibilised and consequently more endangered than before.

Moving Europe, June 2016

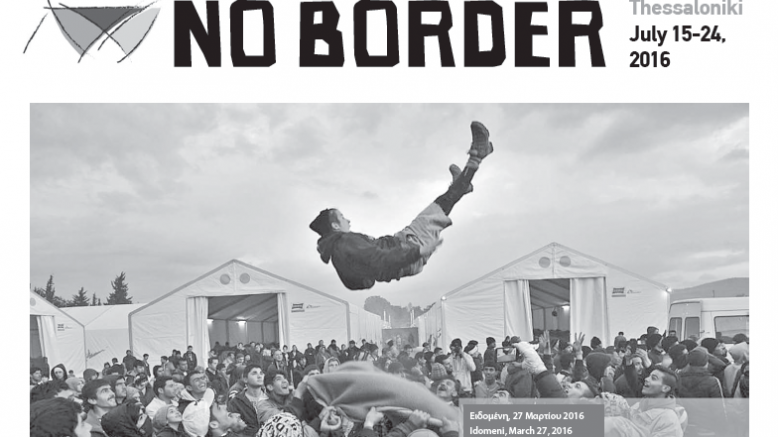

This article was written as a collective contribution to the second issue of the NoBorder Newspaper, and the picture reproduces part of the newspaper cover. For the full publication, see: http://noborder2016.espivblogs.net/files/2016/07/newspaper_NoBo_2_web.pdf