Preface | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7

Summer of Migration – Part 1: Through Bulgaria

PDF-Download: Summer of Migration – Part 1: Through Bulgaria

The West Balkan route, which became the scene of the breakthroughs of marching migrants and refugees during the Summer of Migration in 2015, was of no major importance between 2012 and 2014. It appeared that the Greek government was effectively controlling the situation in cooperation with Frontex: the border fence at Erdine and the patrol boats on the Aegean were forcing migrants and refugees onto the hard and dangerous route across Bulgaria and Hungary. Thousands still managed to cross on this route, mostly young men, who tried their luck despite ill-treatments by the Bulgarian police and violent push-backs to Turkey.

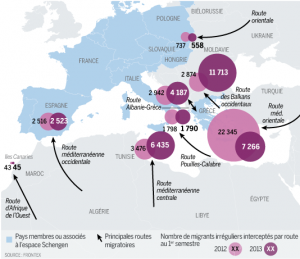

The following map published by Frontex illustrates the situation between 2012 and 2013. As one can observe, the passages on the East Balkan Route had increased to 12.000 in that time frame, and the passages on the West Balkan Route to 4.000. The latter number is equivalent to the amount of passages within a single day in the late summer of 2015.

Image 1: Frontex, Migration to Europe 2012 and 2013

Throughout the course of 2014, the number of transits through the Balkans rose slowly, but steadily. In January 2015, the Bulgarian government decided to build a fence along the Turkish-Bulgarian border.

Swetozar Lasarow, second man in the Interior Ministry and great defender of the construction of the fence, recently pointed out that more than one million refugees are currently staying in Turkey. Their ’natural route‘ to Europe goes through Bulgaria. Lasarow advertised that the fence would regain the construction costs of 40 million Lewa (20,5 million euros) within less than two years, given that the more than 1500 police officers currently stationed along the border could then return to their habitual operation sites“.[1]

From 1st April onwards, the sparse social benefits of €33 per month were removed for asylum-seekers in Bulgaria. The path through the „mire of Bulgaria“ was characterised by push-backs at the Turkish border, police violence and shots at migrants. Nevertheless, between 200 and 300 migrants and refugees were still crossing the border to Serbia every day in October and November 2015.

![Image 2: […] It is secured with razor wire, currently 30km long: A border fence to prevent refugees from Turkey from crossing to Bulgaria. Meanwhile, Syrian refugees report degrading scenes at the external borders of the EU to human rights defenders. […]](https://moving-europe.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Abb.02-300x169.jpg)

Image 2: […] It is secured with razor wire, currently 30km long: A border fence to prevent refugees from Turkey from crossing to Bulgaria. Meanwhile, Syrian refugees report degrading scenes at the external borders of the EU to human rights defenders. […]

Most of the refugees, crossing via Bulgaria, arrive in Dimitrovgrad, a little town, that is 4 km from the Serbian-Bulgarian Border and 60m away from Sofia, the capital of Bulgaria. They have to register at a camp, that is managed by the Serbian border police. Registered people have to leave the country within three days. Some are walking days before they finally arrive the police station. Taxi Drivers are waiting in front and offer a ride to Belgrade for 200 €. Usually they buy a bus ticket to Belgrade for 25 Euro, money that is sometimes provided by volunteers. The volunteers camp is located in the same area as the police station with the tent of the red cross and the presence of the UNHCR. At the end of the working day, the representation of the UNHCR and the Red Cross closed before 4 pm.

Roughly 300 people, later trying to move on for seeking shelter in other European countries, are arriving in Dimitrovgrad day by day. Most of them are young men, nevertheless, from time to time, there are families that arrive with them. Two unaccompanied minors, Jamal and Sami*, explained what they witnessed in the region at the Turkish-Bulgarian border: „We saw two dead bodies laying on the ground. They did not look well anymore. After the police caught us, they were cutting our backpacks.“[2]

Several factors contributed to the westward shift from the inhospitable Bulgarian Route. Surely the most important factor was the elective victory of the Greek party Syriza in 2015, which brought to an end the previous defensive border policies and the cooperation with Frontex; for this reason alone Syriza deserves to be praised. Turkish rubber boat agents reacted to the change immediately. The passage across the Aegean became feasible, even for families and the elderly, for relatively large sums of money. However, it is crucial to put this change into perspective: Instead of one of the daily ferries from Ayvalik (Turkey) to Mytilini (Greece), which costs €25 per head per trip, people were forced to cross the Aegean in rubber boats, for more than €1000 per journey and with the constant risk of lethal consequences.

Of course Syriza was not the paramount reason for the historical rise of passages across the Aegean. Rather, in the fifth year after the Arabellion, innumerable people who had been waiting for an end to the war in countries adjacent to Syria, came to the realisation that their desolate situation would not change in the foreseeable future and returning would continue to be impossible for years to come. Their children would be a lost generation. Moreover, rations in the camps around Syria were being reduced, while animosities against Syrian refugees in neighbouring countries were increasing. In the backdrop of all this was still the self-confidence of a population who had challenged the Assad regime and who was conscious of the right of the Arabellion on its side. Thus, at the micro-level of the evaluations which eventually determine the decision to leave, the possibility to cross the Aegean more easily and relatively safely played an important role, but was not the sole decisive factor.

This chapter does not focus on the situation in Turkey and at its borders, nor on the living conditions for migrants on the Greek Aegean islands. The help from the islands‘ populations, the rescues by fishing boats, the support from international volunteer groups, the implementation of a regular ferry service to the mainland and the subsequent bus transport to Idomeni would be a story for themselves. Part of this story would also be the recent attempts by the Syriza government to install Hot Spots and to drown the large migratory movements in the Aegean with the help of Frontex in the Autumn of Migrations.

However, during the Summer of Migration, refugees and migrants who risked their lives for a better life and a better future, presenting and asserting their Right to Move as an inalienable right, were at an advantage if only because of their large numbers. As they populated the parks and squares of Athens and Thessaloniki, a second Tahrir could have developed, bringing together migrants and battered Greek people, which even Syriza would not have been able to control.

[1] http://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/ausland/eu-aussengrenze-bulgarien-kaempft-gegenfluechtlingswelle-13162853.html, see also http://ffm-online.org/2014/11/05/29257/, http://ffmonline.org/2014/09/21/bulgarien-hungerstreik-und-push-back/

[2] http://bulgaria.bordermonitoring.eu/2015/11/08/silent-crossing-through-bulgaria-ends-up-inregistration-process-in-serbia/, concerning the situation in 2014, cf http://bordermonitoring.eu/wpcontent/uploads/reports/bm.eu-2014-bulgarien.de.pdf